Technology from Sage recently published the latest instalment in our Librarian Futures series of reports, “The Knowledge Gap Between Librarians and Students”. This report focuses primarily on exploring and elucidating a bidirectional knowledge gap that exists between academic librarians and student patrons, highlighting the discrepancy that librarians see the role of the library as more than just a building and a collection, whereas students are largely unaware of or unlikely to use the other services that libraries provide.

If you haven’t downloaded the new report yet, it’s available to download now.

As part of our research, we asked students whether they identified as having a physical or mental disability. Our research highlighted that many students who identify as disabled view the library very differently to students who did not identify as disabled. If the role of the library is to serve patrons, librarians have to ensure all patrons are served equally. Herein we will explore the differences we observed across our data, and make recommendations for how academic libraries might adjust their practices to support patrons who identify as disabled.

Key Findings on the Accessibility Gap

We asked students how easy or difficult they found certain aspects of preparing assignments. Across the following categories, students who identify as disabled reported having significantly more difficulty than non-disabled students:

- Making notes and annotating resources

- Managing my time

- Keeping focused on the task

- Getting help when I need it

- Working on the assignment

This data suggests that students who identify as disabled are experiencing difficulties throughout the entire assignment process. To determine who students are looking to for help, we asked students who had helped them grow across a number of areas. Across the board librarians placed low on the list (below “me”, “my peers”, and “my teachers”), with no significant differences between those who identified as disabled and those who did not.

We then specifically asked students how the library supports their studies. In encouraging news for librarians, very few students reported that it simply did not. Our data did show however that students without a disability were significantly more likely to see the library as a place for collaboration with other students than students who identify as disabled are. Collaborative learning is a crucial skill for students to develop across their time at university, so it is concerning that students who identify as disabled have a different experience of collaboration within the library.

Later, when we asked students to identify where they go to find resources for their assignments and studies, students who do not identify as disabled identified the library building significantly more than students who identify as disabled did. This could indicate unaddressed issues surrounding access.

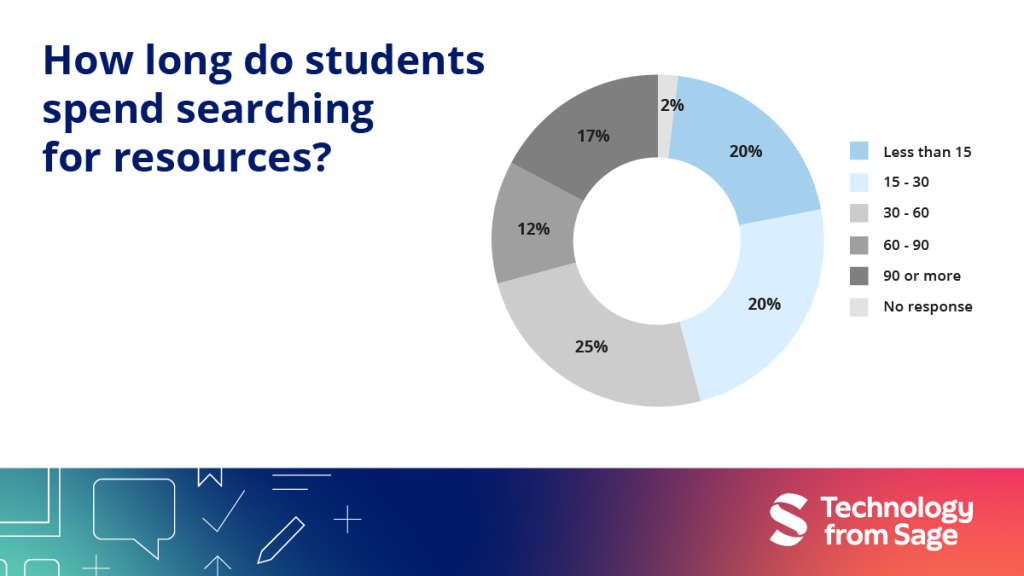

We also wanted to know how long students would continue searching for a relevant resource before moving on for a typical assignment. We found that students who identify as disabled were significantly more likely to spend 15 minutes or less searching before they moved on. Spending reduced amounts of time searching for resources might lead to students missing out on vital research that lends added context to their own work. Understanding why students who identify as disabled are less likely to spend longer looking for resources could help librarians address the issue.

Lastly, we sought to understand whether students were undertaking additional training to support their studies and, if so, how they discovered this. Though we found no significant differences between those who identify as disabled those who do not in whether they undertook such training, we did find that students who do not identify as disabled were significantly more likely to find out about such training from their fellow students, whereas students who identify as disabled are significantly more likely to find out from email communications.

Bridging the ‘Accessibility Gap’

In the first part of our Librarian Futures series, most librarians agreed that the mission of the academic librarian centred around who librarians serve. It is clear from our data however that not all groups are being served equally by the library. Our findings present an opportunity to inform the next steps academic libraries and librarians ought to take.

Librarians Must Involve Students

Our data provide useful starting points for librarians, but they cannot explain the reasons students who identify as disabled do not use the library as often as students who do not identify as disabled. Staff can hypothesise as to the reason, but to address any of these issues, libraries must start with their patrons. The voices of students who identify as disabled must be present and heard in any such conversations: ask students what they want and need and make efforts to meet these requirements. Librarians will then be able to implement targeted measures to address these. Librarians can use a variety of methods to collect student feedback, ensuring diverse perspectives are heard and considered. Librarians might consider running in-person focus groups, as well as online ones. Suggestion boxes or feedback forms will allow students to remain anonymous, potentially contributing to more honest feedback.

Librarians Must Tailor Their Approach

Our data clearly suggests that different groups of students have different challenges at university, and thus it’s clear that no one size fits all approach will be appropriate. Following listening exercises with students, librarians must tailor their approach to ensure specific student groups are being well served by the library.

Librarians Must Enhance Visibility and Outreach

Here at Technology from Sage, we are well aware of the wealth of knowledge and experience that librarians bring with them, and with the academic library as our North Star we stand ready to work with librarians in addressing these challenges. However, given that relatively few students look to librarians for help around their assignments, much of the insight that librarians can offer is lost. By making efforts to raise their profile within their institution, librarians can expect students to approach them more readily.

Librarians might consider running workshops or making appearances at university learning and teaching events. Collaborating with academic staff to embed the library more effectively within the student journey could also be beneficial. Our data suggests that different approaches may be useful for different cohorts of students: the most effective way to reach students who identify as disabled is via email communications.

Conclusion

The data we presented in the latest Librarian Futures should be seen as the start of something, not the end. We have highlighted that those who identify as disabled and those who do not are not having the same university experience, though more work is required to fully understand the root causes behind this. Working in concert, academic libraries and library vendors can gain a better understanding of the challenges students who identify as disabled face, and how we can address these. Together, we can work towards a more accessible library.